Hello everyone, welcome to the journey.

Think of a world where stories explain everything. You’re looking at the moon, the stars, the trees, the ocean. You feel the wind blow, hear the sounds of birds, and see the sun come up every morning. Every phenomenon is connected to a narrative. The moon, for example, is not explained as being this big, rocky globe made of different compounds circling around the Earth. No, the moon is a divine force; a goddess whose goal is to protect us during the night.

And how about the oceans and seas? Aren’t these just massive bodies of salty water; products of millions of years of evolution? Not in this world. In this world, the oceans and seas are governed by human-like gods, home to countless divine beings, such as nymphs and sea monsters and may even be a pathway to the underworld.

And if you encounter a storm when sailing these divine waters, you’re not simply encountering a natural phenomenon caused by air pressure, shifts in temperature, and wind patterns. No, you’ve just gotten yourself into the wrath of the gods, a punishment which, very likely, is because of some bad behavior in the past.

But there were some people not satisfied with these explanations.

This whole idea that human-like gods are the driving force of the universe? These people didn’t buy it. They began to question the gods and every other accepted belief about life and reality. They wanted to understand the world, without relying on narratives which, as they realized, were profoundly polluted by human fantasies. So they started a revolution: a revolution of thought and ideas which changed the way we think forever.

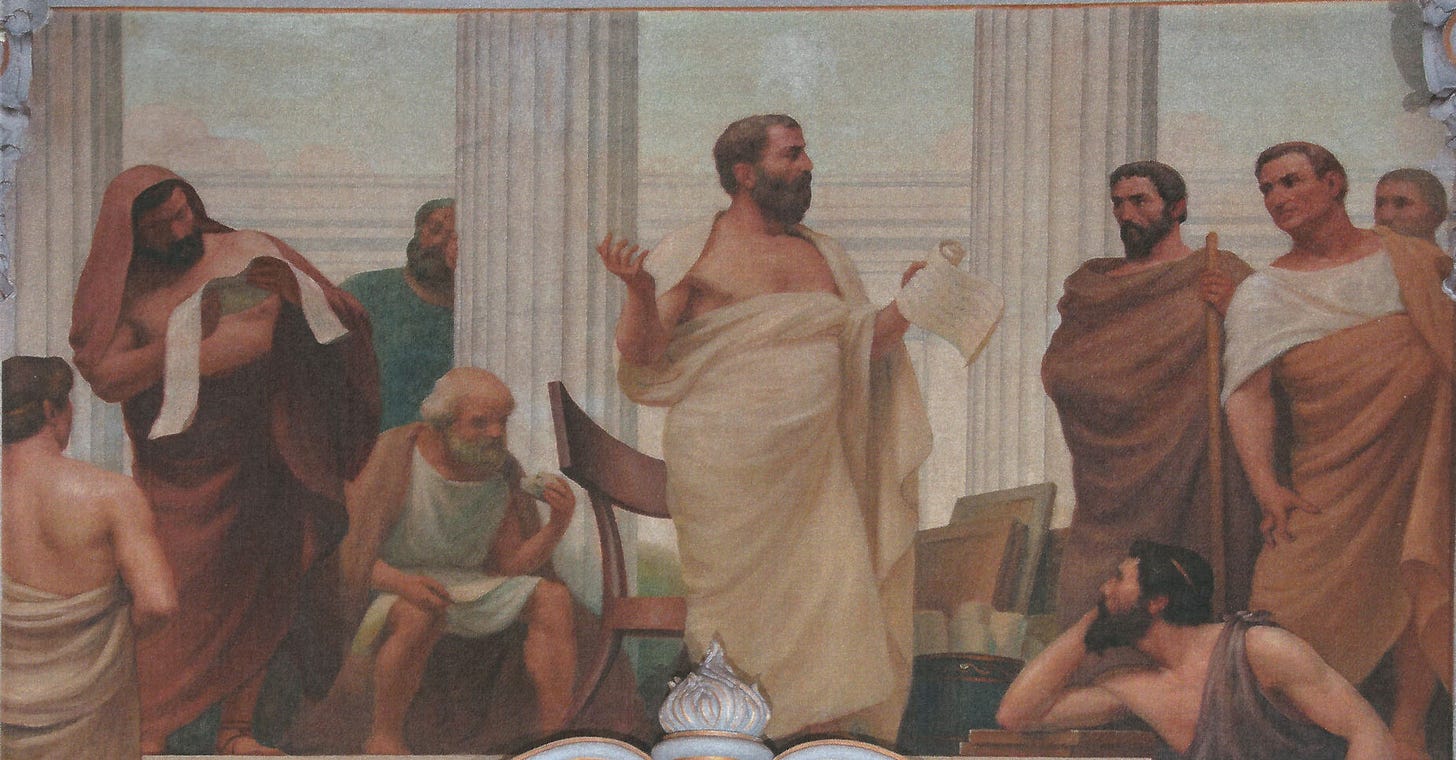

Today we call these thinkers the presocratics, also known as the first philosophers. Among the ancient Greek philosophers, the presocratics are generally less known than figures like Socrates and Aristotle or Epictetus. But without the presocratics, these giants of Western philosophy would probably never have emerged.

So who were these presocratics? Why are they called this way? Where did they come from? And what ideas did they develop? And why exactly are they so impactful?

We’re about to find out in this and the coming episodes.

This is Journey of Ideas, my name is Stefan, also known as Einzelgänger, the creator behind the YouTube channel of the same name. I’d like to take you on a journey through meaning, wisdom, and much more, starting at the very beginning of philosophy. I’m both a fellow-traveler and a guide on this trip, walking beside you. Some of the places we’ll pass through I’ve already visited, others are new to me.

You can see this new project more or less as an Einzelgänger spinoff, starting from the dawn of philosophy. I hope you’ll like this first episode. Let me know if you enjoyed it; any feedback is welcome. For now, you can follow Journey of Ideas without visuals and background music on the platforms Spotify, Apple, and Substack… and with visuals and music on YouTube, in 4k.

This is not an AI voice. I’m a real person. For those watching on YouTube: I don’t show my face, mainly because I want the focus to be on the story, not my personality or appearance. If you want to stay updated about my work subscribe to my newsletter on Substack or on my website journeyofideas.com, where you’ll also find written versions of this new podcast slash YouTube series.

Now, all hands on deck. We’re approaching the shores of ancient Ionia, a Greek colony that once thrived along the Aegean coast of what is now modern-day Turkey. It’s here, in the sixth century B.C., where a profound shift took place: the very beginning of Western philosophy. But our journey won’t be without decent preparation.

Yes, we’re tourists, but not the kind who drift from one spot to the next, unaware of where they truly are, as long as their Instagrams and TikToks are fed. We want to know where we’re going; we want some history and context. At least, I do, because in my experience, understanding a place really brings it to life.

Arriving in Ionia

We’re glaring at Ionia’s coastal region, the city of Miletus during the late seventh century BC to be specific. This was the Archaic period: a time of rapid change in ancient Greece.

Something big was about to start in Ionia.

When learning more about it, I discovered that Ionia is nothing short of a fascinating region. It was located in a part of the world that’s heavily debated today: is it Europe or not? I’m talking about what we now call Turkey.

Ionia was geographically part of Asia Minor, with Europe in the West and the Orient in the East. During the seventh century BC, Ionia was part of the Greek world. The Greeks were also known as the Hellenics.

Throughout the ages, the Hellenics saw themselves as the ideal civilization: manly, spirited, freedom-loving, goodlooking, but also sophisticated, wise, and rational. Studs on the outside, philosophers on the inside. The full package. As a self-declared ideal civilization, they often felt better than others, such as the people from the Orient.

In the eyes of the Greeks, the Orientals (referring to people like the Lydians and Persians) were nothing to write home about. They viewed them as decadent, effeminate, and lacking in vitality and spirit. And people in Northern Europe didn’t fare much better.. Sure, they were fierce and brave, swinging around with their spears and axes… but too uncultured: unfit for the finer things in life, like art, politics, reason and philosophy. And the Greeks had a term for these people: ‘barbaroi’ or ‘barbarians.’

Even though the ancient Greeks admired other peoples in some respects, perhaps for their knowledge about things like astronomy or mathematics, or because of their architecture, they generally weren’t fond of foreigners, often looking down on them based on rather dubious stereotypes.

It is funny isn’t it? Those who create these stereotypes usually place themselves at the top and the ‘Other’ a couple of notches below. And it seems we’re still pretty good at this practice today: in-group preference while diminishing the ‘Other’. The unique location between East and West is partly the reason why Ionia’s history was so eventful. The lands lying in front of us witnessed a plethora of events, cultures, and clashing civilizations. It was subjected to many different rulers from all directions.

The mountains and hills we see in the distance once belonged to the Bronze Age Hittite Empire. After its collapse, local Anatolian peoples and, later, Greek settlers from across the Aegean came in.

Over the centuries, the land fell under the rule of the Lydians and the Persians: you know, the people that the Greeks deemed effeminate and lacking in spirit. Afterwards came other people like the Macedonians, Romans, Byzantines, and eventually the Turks who still populate the region today.

So, as we’re on a journey of ideas, why do we start our trip here, in Ionia? It’s because Ionia was home to what many regard as the very first Western philosophers. The first of the first. These thinkers, who roamed the city during the seventh and sixth centuries BC, were about to unleash a revolution.

But before we discover their stories and ideas, I think it’s essential to learn a bit more about the time and place. We want to know what life was like there, how people lived, what they believed, so we can form a picture of why these first philosophers (and therefore Western philosophy itself!) emerged.

To find out, let’s take a closer look at when and where these thinkers arose.

A Walk in Miletus

We don’t know exactly what Ionia and Miletus looked like back then, or what life was like there. They weren’t uploading photos to some ancient Greek version of Instagram back then. We rely on historical accounts; ancient texts and archeology. So, it’s impossible to visit the real place. But we could at least shape a picture of what we know.

Let’s try to imagine it. Let’s shape a picture of, in this case, a 7th century BC Miletus. And while we do, let’s have a short walk in it. Miletus strikes us as a lively place. Fishing boats roam around. Trading ships come and go; some go westwards, others go into the direction of the mouth of the river; the Meander, to be precise. Some important looking men walk beside the walls that surround the city.

Miletus was an important place, possibly the most important ‘polis’ (which is roughly translated as city-state) in Ionia at that time. It was a cultural center, bustling with visitors from many places.

The air smells of the sea surrounding the peninsula the city is built on. We see architecture, most likely influenced by other civilizations, such as Egypt and Lydia. Most houses are modest, made from mud brick and wood. But here and there, larger structures appear: buildings of importance, where wealthy-looking men come and go.

The streets smell of freshly baked bread, but also of rotting remains of food and waste. It’s crowded. Traders, craftsmen, fishermen, and slaves… mostly men in light-colored tunics. But we also see some strangers here and there; people whose faces and clothing reveal that they’re not from Greece, but from distant lands. They may come from Egypt, Phoenicia or maybe from as far as Babylonia. And the women? Probably inside their houses doing chores.

It’s important to note that most of the ruins visible today at the site of ancient Miletus (including the Ionic Stoa and the theatre) were constructed after the time of the Presocratic philosophers. So, we’re dealing with a city much older than the archeological sites available today.

But temples and shrines were extremely likely to have been part of the city. So, we’re seeing these places rising along the streets; buildings and shrines, dedicated to the gods. In these sacred places, we see people stretching their arms toward the sky, reciting prayers. The air smells of burning fat and bones. Animal offerings were common in those days. These people are honoring the gods… and they’re taking it very, very seriously.

The gods had a special place in the lives of the ancient Greeks. And these gods were many, and some of them are still widely known today. Poseidon, for example, ruling the vast and unpredictable seas. Or Hades, the god of the dead and in charge of the underworld.

For the Greeks, the gods had a huge finger in the pie. For example, whether your harvest would be good or not depended almost entirely on the gods. Whether your children would be healthy depended on the gods. Storms, illnesses, drought and even enemy invasions were simply signs of divine punishment or discontent.

For the Milesians, and probably most of the Greeks of that age, the gods were intertwined with virtually every aspect of life, from business to physical health to weather conditions. All is the work of human-like deities, and thus, you better be on good terms with them, capricious as they were by the way. For us, these views may seem ridiculous, but it was common sense for most Greeks; the most normal thing in the world.

However.

There was also another side to the city of Miletus. As it was such a busy cultural center, it was also well connected to other regions of the known world well beyond Greece, such as Lydia and Egypt. International trade was already there. And even though direct contact between the Greeks and the Chinese was unlikely, it is possible that Chinese silk traveled to Greece, through other civilizations in the East.

Foreigners not only brought in merchandise but also different views about the world. This exposure probably made the Milesians more open-minded than the average Greeks; more willing to explore ideas that deviated from the norm. And thus, an intellectual community arose in Miletus, making it a fertile breeding ground for what we now call Western philosophy. But before we go into these first philosophers, I think it’s important to talk a bit more about the gods.

During our short walk through the city (or at least our reconstruction of it), we saw people at the temples and shrines, the rituals, the prayers, the offerings. But among the inhabitants of Miletus, there were also people who questioned the ideas of human-like gods governing the universe; people not satisfied with the conventional explanations of how the world works.

We could say that the first philosophers started out by challenging the dominant view of their time (and with good reason). To understand the first philosophers, I believe we must also better understand the worldview they challenged. So, what was this worldview exactly? Why did the ancient Greeks see the world the way they did? For example: Why didn’t they just see an ocean as an ocean, instead of a divine realm, ruled by a powerful bearded god with a trident?

Let’s go into this briefly.

The age of stories

Suppose you live in a world without the explanations of modern science; a world vastly unexamined and small, where distant lands are unknown and natural phenomena belong to the great riddle of existence staring in your face at any moment.

You see a volcano erupt, birds flying around in curious formations, insects crawling on the ground, and you think to yourself: What is all this? Why is all of this happening? How does it work? And, by the way… why are we here?

As you’re craving for answers, you pose these questions to the vast, starry sky above, hoping that someone, maybe a voice from the heavens, will answer. But guess what… crickets. And as the human being you are, this kind of bothers you. And you aren’t the only one. The riddle of our existence bothered our distant forefathers, too. And it still bothers plenty of people right now, myself included at times.

Let’s face it. We humans are a curious bunch. We have a strong desire for meaning, which sets us apart from our animal friends. We don’t just want to know where the food is; we also want to know where the food is coming from, what it’s made of, and why we’re hungry, and why it should be like this, you know, feeding ourselves on organic stuff to keep our bodies going, and for what?

Suppose you put some insanely curious beings in a world that doesn’t make sense and doesn’t provide any explanations whatsoever on why everything is the way it is, and why all these strange phenomena are thrown at them. What do you think you’ll get? Most likely, some deeply unsatisfied beings; anxious and desperate to understand.

By and large, humans don’t like it when they don’t understand things. And it’s not uncommon for people (even today) to construct a kind of truth, about something they don’t comprehend, just to find a sense of peace with the unknown, even if, deep down, they’re fooling themselves.

So that’s what they did back then: to understand the world, they began to construct explanations of natural phenomena, of their origins, of life and death; in short, the mysteries that confronted them.

But can you really blame them?

I mean, today we’re kind of spoiled. We have loads of empirical evidence to make judgements about things that we can consider objectively true or false, or, at least, very plausible or implausible.

For example, we now know that the Earth is not the center of the universe, but that it’s an orb rotating around the Sun. How do we know this? Because we can prove it. We also know that lightning occurs when there’s a huge amount of static electricity that’s built up in the clouds, which suddenly discharges. Why? Because we’re able to prove it empirically. It’s not magic. It’s science.

But back then, all these phenomena that are so obvious to us, had to be declared without the methods and knowledge we have right now. And so, these ancient humans, hungry for meaning, resorted to a kind of manufacturing of explanations for the world around them. And they did it in a peculiar way. They began to explain the world by the means of stories.

Stories ease the nagging pain of not-knowing, as they provide answers to questions such as: What’s that glowing thing in the sky? Why does the sea move like that, shimmering under the sun? Why does light turn to dark, and dark back to light? Where do we come from, as a species, but also as an ethnic group, for example? And where are we going after we die?

As a result of their story-telling, whole systems of myth and ritual came into existence. These systems provided narratives that explained the phenomena of the world and told people how to deal with them. So, for a long time, before the emergence of philosophy and science, the ancient Greeks looked at, what we today call, “myth” to make sense of their lives.

These myths weren’t just fairy-tale-like stories about powerful bearded gods living in the clouds or mysterious nymphs guarding rivers and ponds. They were actually quite diverse, and some were even close to plausible historical accounts. In fact, some scholars consider certain myths to be a form of proto-history: early attempts to preserve and explain the past before written history existed.

And the ancient Greeks weren’t alone when it came to using stories to explain the world. The Egyptians did it too, and the Norse people, and the old Germanic people, and the Native Americans, the Aboriginals, the Sumerians, the Indians, the Chinese, the Javanese, and so on. But many scholars would agree that Greek mythology has something special about it: it’s rich, extensive, influential, well-organized and comes in literary masterpieces still widely read today.

I mean, who doesn’t know Zeus, Aphrodite, Hera and the likes? And haven’t most of us heard about the heroic tales of Hercules strangling serpents or Theseus killing the Minotaur with his bare hands? How many films, books and video games are based on (and inspired by) Greek mythology?

That said, a new way of thinking, a post-myth approach to life and reality was looming around the corner. And soon mythology would be accompanied by what we now call ‘philosophy’. But how did this happen? Let’s explore this right now.

Of Greek religion

When talking about ancient Greek mythology we cannot ignore two individuals; two poets whose works helped to turn this vast collection of local myths and beliefs into a more coherent corpus, so to speak. The guys we’re talking about are Homer and Hesiod.

Homer and Hesiod were from ancient Greece and lived in the eighth and seventh century BC. Though it’s debated whether Homer truly existed or if his works were actually compilations of other poets. But we’ll ignore that for now.

What’s so special about Homer and Hesiod?

They created the first surviving Greek written poetic works, and their writings offer the earliest detailed accounts of the gods and Greek mythology. It’s not that they invented Greek mythology. Greek mythology, although fragmented and unsystematized, already existed long before Homer and Hesiod.

Enter the Mycenaeans, who are considered the first advanced Greek civilization and flourished from around 1700 until 1200 BC. Yes, that’s quite a long time ago. They existed way before Homer and Hesiod.

The Mycenaeans had myths and worshipped many of the same gods we know from the later Greeks. But they didn’t write anything down about their gods: their script, known as Linear-B, was only used for administrative reasons, such as writing down how much grain was in the barn, or to list important people. Their mythology was passed on through ritual and spoken word, although there are written records of names of the gods.

When the Mycenaean civilization collapsed and their Linear B script faded into obscurity, Greece slipped into what we now call the Greek Dark Ages. Myths survived, but in spoken word, not in writing.

At the end of the Dark Ages, a new time began: the Archaic period. During the Archaic period, Homer and Hesiod dropped what would become the foundational texts of Greek mythology, that, in essence, repackaged the old gods into the Olympian versions.

We know Homer from his epic poems the Iliad and Odyssey. Revisiting these works recently, probably since high school to be honest, I realized how entertaining they actually are. The Iliad tells about the Trojan war, the anti-hero Achilles, Hector and his brother Paris, and many more characters, and the active involvement of the gods in the whole event, which supposedly lasted ten years. The Odyssey (which I enjoyed slightly more) is an adventure of the witty king Odysseus, meeting misfortune after misfortune, as he tries to return to Ithaka. The gods play a huge role in this story.

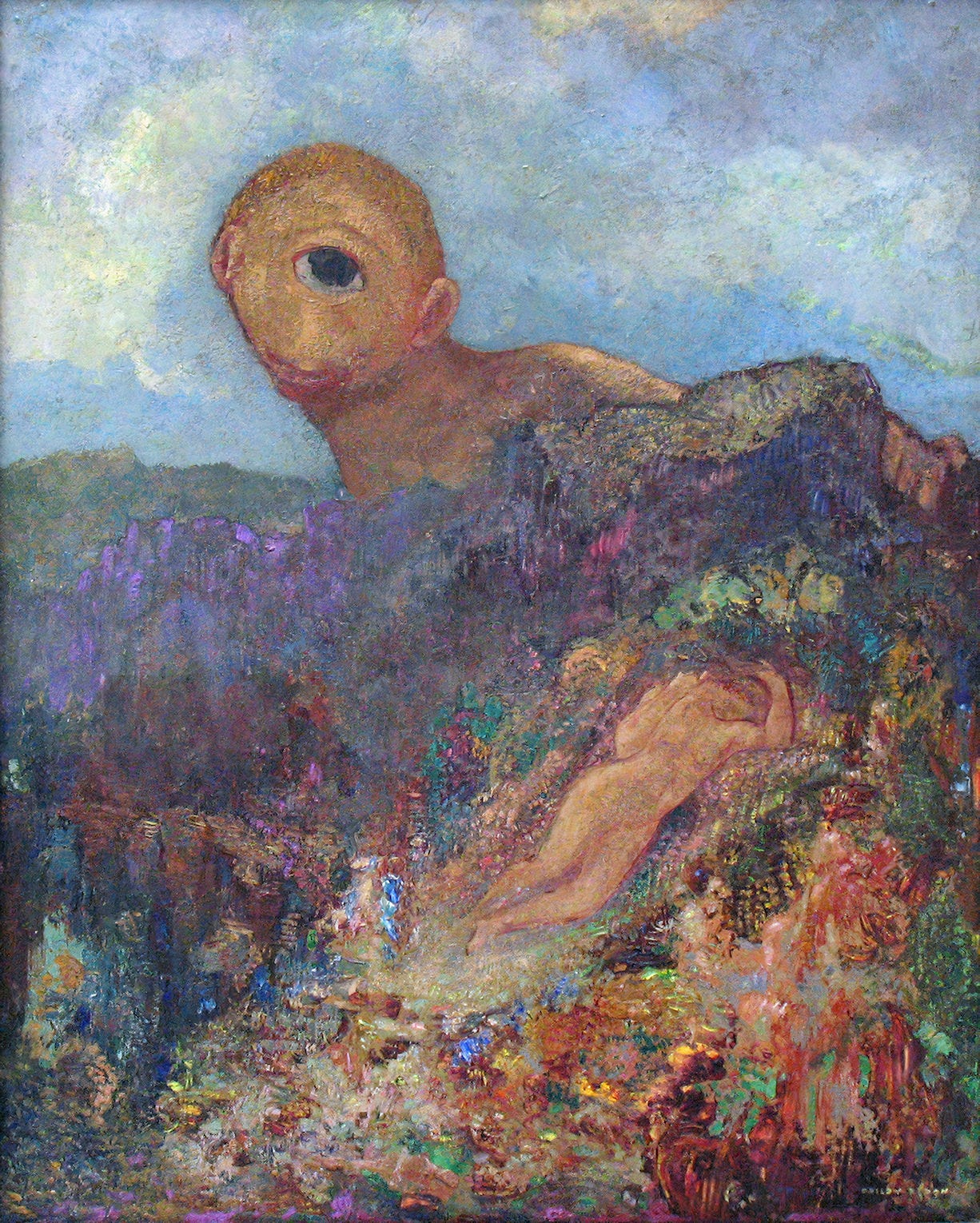

We also meet with mythical monsters like the Cyclops, which are giant one-eyed beings or Scylla; a monster with six dog heads living on a rock; definitely not a creature you want to encounter on a journey across the sea. We also get a peek into the underworld; a dark, cold, depressing place.

Hesiod is lesser known than Homer and wrote entirely different works. Instead of epic stories, Hesiod wrote a systematic description of the origins of the gods in a very influential work named the Theogony. The Theogony, which fundamentally tells the creation myth of the Greek pantheon, presents us with not only the gods, but also many other divine entities, such as the primordial beings Gaia and Tartaros, who personify the Earth and the underworld. It also tells us that these primordial beings gave birth to the Titans, and the Titans gave birth to the Olympian gods.

What’s so striking about Hesiod’s work and the mythology it represents is that it paints a deeply ‘animate’ universe. Almost everything is personified. Natural forces are human-like with similar temperaments. They were gods, individuals with their own will, who could hear your prayers and might even speak to you, if only they appeared in the flesh. They were all part of this large, mighty family of immortal beings, many of whom dwelled above the clouds on top of Mount Olympus.

Hesiod makes it all clear and easy to follow for the average Greek. He may not be as entertaining as Homer but he’s certainly informative. Think of it like watching Homer’s epic blockbuster and then searching for in-depth, systematic explanations in a special wiki dedicated to that movie. That wiki is Hesiod’s Theogony.

Both Homer and Hesiod’s writings were held in high regard in ancient Greece. They were a go-to source for understanding the world; especially the gods, from Zeus and Hera to Athena and Apollo. The temples we saw in Miletus are dedicated to these gods; divine forces upon whom the fragile lives of mortals completely depend (at least that’s what people believed). And as becomes clear when reading Homer and Hesiod: these gods aren’t perfect beings. They are definitely not role models like Jesus or Buddha. They are often cruel, envious and whimsical. They are human-like; flawed inside out.

Just imagine your life depending on such beings. The people in the temples must have feared them. Your best bet would be to keep them happy, right? Hence, the many rituals, prayers and offerings, as they hoped that by appeasing them, they’d get good fortune in return, such as a decent harvest or victory in battle.

By the way, if this all sounds a bit like religion to you, you’re not alone. Even though religion is a fairly modern concept, the ancient Greeks did engage in practices and held beliefs that we today consider religious. Or, if you allow me to flex my religious studies jargon; there was a lot of religiosity at that time, which had many perks akin to what religion means for people now: it explained the world, there were supreme beings to worship, it gave people a sense of meaning and place, it functioned as social cement, and it provided a feeling of control.

So, we can say that the ancient Greeks were pretty religious. But their form of religion differed from, say, Christianity or Islam: there was no holy book, no central doctrine, no fixed articles of belief. Instead, it was a blend of stories and rituals, and both the practice and the content of mythology varied depending on the place. Moreover, each Greek city had its own local myths and heroes, often explaining the origin of the city and its people.

Now, why is all this important? What has all this information about mythology and religion to do with the rise of the first philosophers?

We’re about to find out.

The presocratics arise

Attaching stories to natural phenomena may seem to us like a practice of ignorant minds. Like, who believes this stuff? Who believes that the Sun is actually a guy in a chariot named Helios? Or that way up there above the clouds, on top of the mount Olympus, Zeus, the king of the gods lords over the Earth? And that all natural phenomena we see, all animals, seas, beaches, trees, plants, the weather; are either personified or governed by these, again, human-like gods?

Just imagine being a bit sceptical of all this, watching people go in and out the temples, hearing people pray from a distance. You witness goats and pigs offered at shrines and altars everyday. You see your fellow citizens taking part in sacred festivals where drinking wine is a ritual: a tribute to the mad god Dionysus. And you think: “Why? Why have we explained the universe using these capricious gods for ages? I’m sure we can do better.”

Our forefathers and their forefathers may have been passing on these stories like a torch of eternal fire. But do these stories, how familiar and soothing they may be, really contain the truth about things? Or do they divert us from what’s really going on like a warm, comfortable blanket shielding us from how things really are?

What if these gods are not what we believe them to be? What if we put the conventional understanding of the divine aside for a moment, and see if we can explain the universe without appealing to the gods? Here’s where the presocratic philosophers entered the building. Or temple, should I say?

These thinkers wanted to explain reality based on natural principles instead of mythological stories. Of course, this was huge! They were at the start of a whole different way of thinking. They tried to understand the world through natural causes, instead of using stories about gods like Homer and Hesiod did.

But, why the name ‘presocratics’?

It has something to do with a guy named Socrates. You might have heard of him. He’s regarded as one of the greatest philosophers ever lived; so great that in academia they began to make a distinction between those before him and those after him. A bit like we do with Christ; there’s a time before and after Christ, as if he was the beginning of an era. He was, in fact. And so was Socrates.

But Socrates wasn’t a self made man entirely: he built upon something. That something, that foundation that not just Socrates but countless other philosophers also used to shape their unique ways of seeing the world, was laid there by the presocratics.

The first one of them, Thales, was from Miletus. Then came Anaximander and his pupil Anaximenes, both from Miletus as well. Then, there was Pythagoras from Samos and his curious cult. Then came Xenophanes, Heraclitus, Parmenides, Anaxagoras, Empedocles and several more after and in between. They asked themselves all kinds of questions like:

How does the universe really work? Do gods really exist? Or is there, perhaps, just one God or first principle?

Truth be told, trying to find answers to questions like these is pretty ambitious. How do we even attain this knowledge? Could we find answers by changing the way we think? Is there actually a right way to think about things and what would that be? And are there limits to our knowledge?

The presocratics wanted rational explanations. They marked the transition from mythos to logos: from attributing nature to gods to understanding nature through observation and reason. By and large, they didn’t completely reject the idea of gods or the divine, but they didn’t want to rely on the conventional Greek pantheon laid out by people like Hesiod anymore to explain things.

I want our journey to cross these philosophers and places they lived, because I think their efforts are admirable and their work is significant, even though many of the theories they came up with were pretty implausible and, sometimes, downright bizarre. But it’s intriguing, in my opinion. It’s food for thought. And we might even encounter some profound wisdom in their actions and ideas. I also want to take a look at the sophists, a group of philosophers who built on the works of the presocratics and were met by the people with mixed responses.

If you’re with me, stay aboard. In our next expedition, we’ll go ashore for a second time and meet with the ideas of the rebel thinkers of Miletus, starting with Thales, who came to the conclusion that everything comes from water. And, if we’d believe the historian and philosopher Plutarch, Thales held a personal conviction that marriage and children just isn’t a good idea.

I hope to see you then!

Thank you for listening.

Sources

The First Philosophers (Robin Waterfield)

A Presocratics Reader: Selected Fragments and Testimonia (Patricia Curd, Richard D. McKirahan)

Philosophy Before Socrates: An Introduction with Texts and Commentary (Richard D. McKirahan)

Early Greek Philosophy (John Burnet)

The Iliad & The Odyssey (Homer)

Foundation Myths and Politics in Ancient Ionia (Naoise Mac Sweeny)

Presocratic Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction (Catherine Osborne)

Theogony and Works and Days (Hesiod)

Greek Myths & Tales (Richard Buxton)

Online sources

https://www.britannica.com/topic/pre-Socratic-philosophy

https://iep.utm.edu/presocra/

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/presocratics/

https://www.worldhistory.org/mycenae/

https://sites.utexas.edu/scripts/files/2020/06/2008-TGP-MycenaeanReligion.pdf

https://www.worldhistory.org/Greek_Dark_Age/

https://www.fhw.gr/choros/miletus/en/sources.php

https://www.fhw.gr/choros/miletus/en/index.php

https://www.fhw.gr/choros/miletus/en/arxaiki301.php?menu_id=3&submenu_id=301