Welcome to the journey.

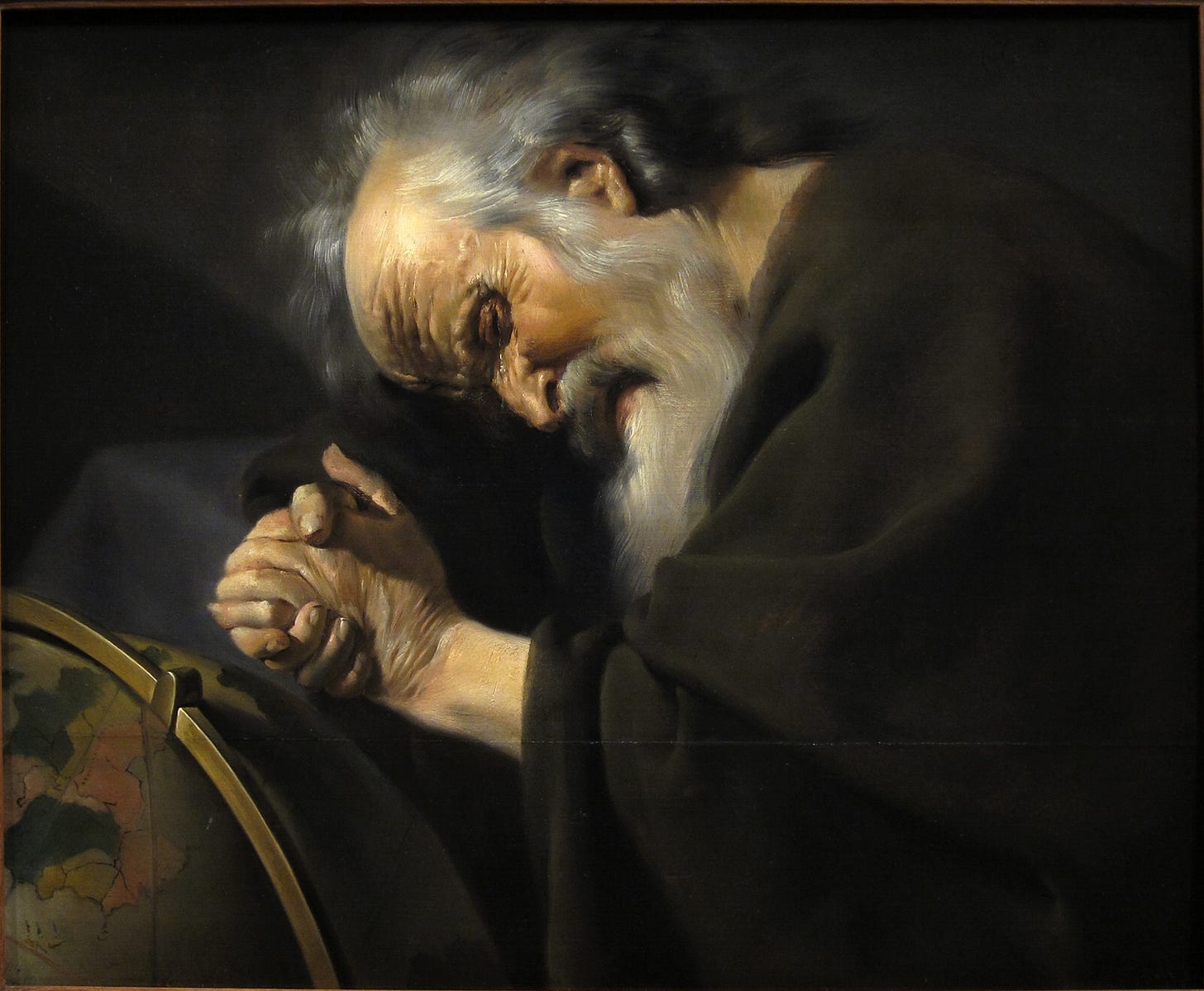

Heraclitus is often depicted as a solitary figure who despised people’s ignorance and turned his back on public life in Ephesus, the ancient Greek city where he lived. Stories tell that people saw him as mysterious and eccentric. He was mysterious because what he said and wrote often didn’t make sense to people, which earned him nicknames such as ‘The Riddler’ and ‘The Dark’. He was eccentric because he refused to follow the conventional ways of living. He lived a solitary life, possibly in the mountains, with little social interaction.

Comparable to the philosopher Pythagoras, stories about Heraclitus’ life are plentiful, but hard facts are pretty scarce: for a significant part, he remains a mystery. Yet his work has been highly influential, and later thinkers such as Aristotle, Plato, and even the Stoic philosopher Seneca have speculated about what his strange, ambiguous words actually mean.

From what we can see from the remains of his work, Heraclitus was very much concerned with change. Whereas others saw the cosmos as more static and monolithic, he perceived an ongoing interplay among forces, matter, and elements, making it ever-changing

However, the changing nature of the cosmos wasn’t the only thing Heraclitus was interested in. Like his predecessors, he also had ideas about the fundamental principle of everything: the arche.

His big frustration seems to be that, even though he dedicated his whole life to examining reality and came to profound conclusions about how things actually work, people refused to listen because they were too immersed in their daily affairs.

In this episode, we’ll take a look at the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus, his ideas, his work, and his life.

****

This is Journey of Ideas. My name is Stefan, also known as Einzelgänger. This is not an AI voice. I’m a real person. And I’m taking you on a long trip.

We’re exploring the ideas of the many great thinkers of history, as well as the times and places in which they lived. Right now, we’re at the very beginning of Western philosophy.

This episode is available as an audio podcast on Spotify, Substack, Apple, and several other platforms. To stay updated on all my content, subscribe to my newsletter on Substack or journeyofideas.com.

I hope you’ll enjoy this episode.

We’ve been hanging around everywhere and nowhere when exploring the skepticism of Xenophanes in the previous episode. Now, we’re setting course for a coastal town in a region we’ve visited before, Ionia, which was located on what’s currently the west coast of Turkey.

We’re still in the 6th century B.C. Watching from the deck, we see a large portcity. Trading ships are coming and going. Greek colonists had been settling there for centuries before, but around 560 B.C., the Lydian king Croesus barged in and plundered it. About 25 years later, this city, Ephesus, gave birth to Heraclitus, another Ionian philosopher who would change the way we think forever.

What do we truly know about Heraclitus? Again, there are many stories, but little factual information exists. One of the books I used to learn about this philosopher, a Dutch translation by Ben Schomakers, includes extensive notes to give the reader a better grasp of Heraclitus’s often puzzling language.

The book is called ‘Alle Woorden’ (All Words, in English) and tells us that, aside from some already dubious historical information about his birthplace, we simply don’t know who Heraclitus is. All we’re left with are a series of fragments and later accounts; material that cannot be fully verified and can only be understood through interpretation.

Hence, some stories about his life could be true, others are likely fiction. But I do think they’re amusing no matter what, and shape not necessarily who he was, but at least how he’s been perceived throughout history.

As said, Heraclitus has often been portrayed as a solitary guy with misanthropic tendencies. We don’t know whether he truly despised people or just showed tough love through harsh criticism. But from the fragments that remain, I got the impression that he didn’t have high regard for the ordinary people. He said things like:

Eyes and ears are bad witnesses for men if they have souls which cannot understand their language.

F27 (DK 22B107; KRS 198; W 13; M 13; K 16) (Sextus Empiricus, Against the Professors 7.126.8–9 Bury)

And:

May your wealth never fail you, men of Ephesus, so that your baseness may be exposed!

F57 (DK 22B125a; 96; M 106) (John Tzetzes, Notes on Aristophanes’ ‘Wealth 90a, Positano et al. p. 31)

Heraclitus comes across as feeling misunderstood and perhaps frustrated by the ignorance of his fellow Greeks. He seemed to believe that he possessed wisdom that others didn’t. He criticized Homer, for example, for not understanding the underlying nature of day and night (which we’ll talk about later), and that he deserved to be whipped for this.

And Homer wasn’t the only one who deserved punishment according to Heraclitus: Archilochus, an early poet from the Seventh century, needed a beating too, although we don’t know exactly why. He also ridiculed Pythagoras for being knowledgeable about many different subjects but lacking in wisdom. So, it’s not that surprising he’s often portrayed as a grumpy, misanthropic guy.

As his predecessors likely did before him, Heraclitus must have walked around his hometown with suspicion. He saw his fellow Greeks worshipping these humanlike gods, performing these weird rituals. And he criticized them, for example, by comparing praying to statues to chatting with a house, saying that people engage in such practices because they’re ignorant of the true nature of gods. His skepticism and criticism of conventional religion align him with Xenophanes, whom he probably never met but likely knew about, as he mentioned his name.

So, Heraclitus criticized those who, according to him, didn’t attain true wisdom. But what is wisdom? What is the truth? And how can we obtain the truth? He seemed to believe he was pretty close to understanding how the cosmos (or what we’d now call the universe) works, though his delivery was quite confusing. He wrote in riddles, paradoxes, metaphors, and aphorisms, which lends his writings to ambiguity and multiple interpretations.

Even though only fragments remain, historical sources suggest that Heraclitus wrote a single work: a book. And this book was apparently so difficult to comprehend that, as it’s said, it needed “Delian diver not to be drowned in it”. It’s almost as if he purposefully tried to make the truth hard to obtain, as if his readers needed to do a significant amount of work to get it. “Those who seek for gold dig up much earth and find a little,” said Heraclitus.

Or, maybe, he avoided clear, rational explanations, and instead wrote as he did, because what he tried to conceive goes beyond human intellectual understanding, meaning that he didn’t want to explain anything, but just point; point to something much larger than ourselves, for which human language isn’t enough to describe it. He would refute himself if he did describe the undescribable, as Professor Angie Hobbs suggests in her fantastic talk on Heraclitus (to which you’ll find a link on my Substack page).

Now, what was it that Heraclitus wanted us to understand? Let’s explore his work in several different ‘themes’, starting with what seems to be the cornerstone of his philosophy, the Logos, and continuing from there.

I’d like to emphasize that I’m not an academic scholar of pre-Socratic philosophy or something like that. This isn’t an academic paper, but rather an informed exploration by a philosophy enthusiast who loves drawing outside the lines, meaning I like to expand on ideas that I find interesting and see if they’re relevant to our daily experiences; something I’ve been doing for years on my YouTube channel, Einzelgänger.

Logos

Now, who or what governs all this? This is a question that the Presocratic philosophers pondered for a long time. And according to Heraclitus, all people before him who tried to answer this question were wrong, and he, himself, was right.

He argued that Pythagoras lost himself in mathematics; Homer and Hesiod told stories, but neither really found what they were looking for. In one way or another, they sought the truth about the nature of the world. Hence, the Milesian Presocratic philosopher Anaximander proposed the ‘apeiron,’ Anaximenes argued that the first principle of everything is air, and Xenophanes believed God is a single supreme being. But according to Heraclitus, descriptions such as theirs couldn’t really grasp the truth behind it all, which he himself referred to as the ‘Logos’.

When trying to at least superficially grasp what Heraclitus actually meant by ‘Logos,’ I found different interpretations. Some, like John Burnet’s, point to a more rational principle; something that the Stoics later developed to become their own explanation of the Logos.

Others, like Ben Schomaker’s, speak of something more like a voice of reality, heard within oneself as a voice of wisdom, telling what to do in the here and now, tailored to each individual. At least, that’s how I understood it. From what I’ve found, we can safely say that, for Heraclitus, Logos is a higher force, perhaps even divine, that brings order to the cosmos, what we could anachronistically call ‘the universe’.

The problem Heraclitus repeatedly seems to raise is that people are not in tune with the Logos speaking within them. They are “asleep,” as he says, and therefore they block their own access to a higher understanding. “The Logos, like the whole world, common — accessible to all — and yet we fail to see what is right before our eyes,” as Robin Waterfield describes it in his book The First Philosophers.

Unfortunately, Heraclitus doesn’t offer a step-by-step practical guide to accessing the Logos. And that’s what frustrated later philosophers about him; his writings are obscure and unclear. I mean, this guy, who was so critical of other people’s claims on this matter, declaring he knew how things worked, but then came up with a collection of riddles even geniuses like Plato and Aristotle couldn’t make sense of… that’s pretty wild, isn’t it?

But when we think of it… How can we describe something so profound and obscure? How can we reduce reality to a bunch of numbers and formulas or simple theories? Reality is difficult to grasp, and that’s what Heraclitus seems to want to show with his writings. The reason he never describes or explains the Logos in detail may be that it’s simply too difficult to capture in words.

He merely points at it. And that’s why he tells us not to follow him, but what he is referring to: the word that always is, yet remains unnoticed: “not before they hear it, not when they hear it, even though everything happens in accordance with it,” he wrote.

Even though Heraclitus didn’t explain the Logos itself, he did, more or less, explain its workings and manifestations, or the way Logos shows itself in the world, albeit in his usual metaphors and paradoxes. One of these manifestations is how all things appear and function in opposites.

Opposites

Things function and exist as they do because of an interplay of opposites and the tension between them. Heraclitus described the tension between opposites with the metaphor of the bow and the lyre. The tension makes both instruments functional. But it wouldn’t be there if there weren’t a pull in both directions. When you pull the string of a bow in one direction, the bow itself pulls back in the opposite direction. Now, through this tension, the manifestations within the world are possible.

Take a road, for example. A road goes up a mountain. But it also descends from the mountain into a lower area. It’s still the same road. And it only exists because there are two points it connects. If one of the two sides were to cease to exist, there wouldn’t be a road!

The same goes for day and night, winter and summer, and war and peace. One thing wouldn’t appear without the other. Without day, there wouldn’t be night. Without winter, there wouldn’t be summer. Without war, there wouldn’t be peace. And so, doesn’t that mean that opposites are parts of the same? Can we speak of unity between opposites, a unity essential for the existence of, basically, any phenomenon we encounter in the world?

According to Heraclitus, humans fail to distinguish the unity of opposites. Take, for example, the gods Dionysus and Hades. One is full of life, the other symbolizes death. But Heraclitus mentions that people fail to see that they’re one and the same. Because how can there be life without death, and how can there be death without life? So, why do we celebrate the former and mourn the latter?

We often see people fond of one thing and averse to the other. We celebrate birth, but mourn death. We like wealth and comfort, but fear poverty and struggle. We highly esteem peace and prosperity but loathe war and hardship. But to Heraclitus, these distinctions don’t make sense as there cannot be one without the other. It’s as absurd as loving a mountain top but hating the foot of the mountain: there wouldn’t be a top without a foot. In fact, there wouldn’t be a mountain at all. For anything to exist, there must be opposites.

And precisely because any opposite has its play in the universe, we can’t categorize any of them as simply good or bad. Their value is relative, as we can easily see when we place ourselves in various situations and crawl into the skins of different beings.

As Heraclitus observes: “The sea is the purest and the impurest water. Fish can drink it, and it is good for them; to humans it is undrinkable and destructive.” The same applies to acts that involve physical harm, which we generally see as wrong, but physicians who cut and stab, causing extreme pain in their patients, get paid for it.

Thus, while some things may appear good while others may appear bad from a particular perspective, they are just different sides of the same coin.

So, Heraclitus’s observations have huge implications for how we judge the world, which is often quite one-sided. We tend to view the world from our own unique perspectives. A strong example he gives is that our current ‘state’ shapes how we appreciate things: a healthy person may not think twice about how fortunate he is, and goes on to complain about various daily affairs. But a sick person will see health as very desirable, longing for it and wishing to regain it above all else.

We can approach our ‘moods’ in the same way. How we feel impacts how we see the world. When we’re angry, we see things differently than when we’re cheerful. When we’re hungry, we desire food, but when we’re full, the mere thought of another meal may make us feel sick.

So, our judgments depend on our situations; our mental and physical states, our desires, our interests, and convictions. And as these things are always changing and vary from person to person, so do our judgments. Hence, Heraclitus remarks: for people, some things are good and bad, but for God, everything is good and just.

Now, what characterizes the interplay of opposites is ongoing change. We don’t just encounter a mere diversity of things, like different species or weather conditions. Things also change continuously. Everything is always in a state of becoming, including ourselves.

Flux

Heraclitus is best known for his observation that everything is in flux. “Panta rhei,” everything is flowing, are the famous words associated with him, although there isn’t any proof that he ever said those words, which supposedly come from Plato. But when we look at what Heraclitus said about change, we’ll see that the saying “everything is flowing” fits quite well.

“On those who step into the same rivers ever different waters are flowing,” Heraclitus said. Or something along those lines, because there’s no real consensus about which version of the saying (and there are several) is the correct one. Another version is: “You cannot step in the same river twice.”

Now, what did Heraclitus mean by this? How come we cannot step in the same river twice? How so are different waters flowing in the same rivers? And what does the river stand for?

Several later philosophers tried to make sense of the river metaphor. A popular interpretation is that, as the river is always flowing, whenever we step into the same river, the water is always different. The water we stepped into a couple of days ago may already have reached the sea, and the water we step into today is still on its way there.

So, what does the river stand for? From what I’ve found, it stands for basically everything; a reality in constant flux. Everything means not just stuff out there in the world, but also ourselves. Reality changes, and we’re changing with it.

Now, again, see what implications this has on our lives. When everything is changing all the time, something that has one form now will have a different form later. This also applies to our mental and physical states.

One day, we’re healthy and are concerned with daily affairs like careers and dating, and the next, we’re severely ill, and the only thing we want is to get better. One moment, we’re in a good mood, and our noisy neighbors are just background noise. The next moment, we’re in a bad mood, and our noisy neighbors are the worst thing, completely ruining our lives. These inner states are always in flux.

When we realize that nothing stays the same, we also understand that expecting things to remain as they are is pretty unrealistic, even though many people desire it: they want the good to stay as it is, and the bad never to occur.

Take, for example, relationships. In the early stages, we see each other through rose-tinted glasses. Everything is beautiful, and we may even experience a perpetual high during the days of being in love. However, this infatuation almost always subsides. And so we see that relationships pass through different phases.

When people eventually marry, despite the fact that marriage is supposed to be a permanent commitment, the change still continues. The people who enter the marriage are not the same people a couple of years later, and the circumstances in which they are married might be radically different.

Now, does that mean that something like marriage is antithetical to what Heraclitus proposes? When everything is in flux, what’s the point of making permanent commitments like marriage? After all, the person you’re committing to won’t be the same person anyway, so what are we doing?

But here’s where Heraclitus’s river metaphor gets interesting.

The river doesn’t just stand for the flux of everything. It also stands for identity. Sure, this may sound a bit strange and unexpected; it surely did for me when grappling with this concept. But think about this question: Isn’t the river a river because it changes?

I mean, we can agree that the river’s content constantly changes, and thus we never step in the same waters twice. But isn’t it so that without change, it wouldn’t be a river to begin with? Isn’t change what makes a river a river? And with change, I mean: an ongoing stream of water going from point A to point B? And so, can’t we say that change is an essential part of the river’s identity?

What Heraclitus seems to get at is that everything is in flux, but flux is also the basis of all things. No ‘thing’ is fixed; there are only processes. They’re continually becoming, which is what makes a thing a thing and a being a being. We only have to look at our bodies to see that such a worldview makes sense. What’s a human? Is a human a monolithic, unchanging being? Or is it an ongoing process? And isn’t our ever-changing nature what makes us human? Aren’t the immensely complex processes of our bodies what make us alive and thus grant us our identity?

Coming back to the concept of marriage… Isn’t marriage, like the river, an ongoing process rather than a fixed, immovable thing? Isn’t change, meaning, the challenges you face together, feelings for each other that develop and deepen over time, changing circumstances, the physical and mental alterations of both spouses, to the coming and raising of children, what makes marriage marriage?

Heraclitus didn’t set marriage as an example to illustrate his idea (and I mean the idea of change as identity). But I do, as I think it does it quite well. So, let’s dissect this example a bit further. When we marry, we commit to something permanent; it’s a sacred bond between two people, based on a promise to “do” life together and stay with each other through thick and thin.

The marriage has an outer form, the ‘mold’, so to speak, which gives it a permanent identity. But the content of the marriage is fluid. It’s an ever-changing series of experiences: from moving from house to house to getting grandchildren to crises and hardships. Like the river, it’s always changing, yet stays the same. It may be unchanging on the surface level (or on paper), but the underlying reality is that it’s in a constant process of transforming and becoming. This flux is what makes marriage marriage; if there weren’t flux, what would marriage be?

And so, the river may be different every time we step into it; it nonetheless remains a river. We could say that there’s a difference between how we experience something and the ontological facts about the river.

We experience a river as one, distinctive, identifiable phenomenon: a body of water, streaming from a higher to a lower area, often ending in a sea or lake. Most rivers are stable enough to last for centuries, sometimes millennia, so why not give them names, as they’re pretty effective markers in terms of geography? Yet, on an ontological level, none of these rivers remains the same; in terms of substance, the change is continuous, despite occurring within a seemingly stable form.

But you may wonder: The idea that everything is in flux and that all things arise from an interplay between opposites, all governed by a divine force called Logos, making things appear, move, transform, perish, and so forth… it sounds all very glamorous and beautiful, but how does this actually work?

Fire & strife

In earlier episodes, we’ve explored the idea of a fundamental principle, an underlying element or force from which everything derives, also known as ‘arche’. For Thales of Miletus, the arche was water, for Anaximander it was ‘apeiron,’ for Anaximenes it was ‘air,’ for Pythagoras it was number. How about Heraclitus? Did he propose an ‘arche’ as well? And if so, what was it?

Like his predecessors, Heraclitus also rejected the Homeric gods and sought a rational explanation for the world, rather than a mythological one. As we’ve seen before, he came up with the Logos. So, how does this supposed ‘Logos’ operate? Is there some god pushing the proverbial river forward? Is there a specific element that lies at the basis of all these changes, movements, and transformations? When existence hinges on tension, what causes the tension? Who’s pulling the string of the bow?

For Heraclitus, there is an underlying element to everything, but it’s neither water nor air: it’s fire. Now, did he just try to be original here, or does fire as a fundamental principle actually make sense? How could something that usually brings about destruction be the fundamental stuff of everything?

The thing is that Heraclitus saw destruction as an essential element of becoming. Everything changes, and when doing so, things perish and come into existence. So, it’s not at all weird to see fire as the basis for all these transformations, akin to how a blacksmith uses fire to melt metals and forge tools, such as swords and axes. How Heraclitus exactly saw fire as the arche, we can only speculate, as all we’re left with are riddles on the matter, like:

Fire lives the death of earth, and air lives the death of fire; water lives the death of air, and earth that of water.

Or:

The transmutations of fire are, first, the sea; and of the sea, half is earth, and half the lightning flash.

Scholars I’ve come across describe Heraclitus’ fire not as a passive substance from which everything arises, as in Thales’ primordial ocean, but as an active, dynamic principle, closer to a ‘force’ or ‘process’. Fire is active. It brings things into being through change and also destroys them, transforming them into something else. Elements like water, wind, and earth come and go like this as well, owing their existence and demise to fire as the transformative force.

“Fire coming upon all things will sift and seize them,” wrote Heraclitus, treating fire as a kind of currency: exchanged for everything that comes into existence, and returned for everything that perishes. “All things are an exchange for Fire, and Fire for all things, even as wares for gold and gold for wares,” he wrote.

For Heraclitus, destruction is as important as creation. The process of change is one of becoming and perishing, mediated by fire, governed by the Logos. At least, that’s how I’m currently ‘making it make sense,’ and it’s probably too simplistic, because if it were as straightforward, Heraclitus would have said so, wouldn’t he? Nevertheless, based on what I read from the experts, I don’t think I’m entirely off the mark here.

Delving more into Heraclitus’s process of flux, we discover that he had a thing for conflict. Events we usually consider bad, such as war or other forms of dispute… this Presocratic philosopher embraced them. Was it out of a wish for humanity to destroy itself? Was it sheer sadism, perhaps? Unlikely.

Heraclitus scolded Homer, whom he thought had failed to see the unity of opposites. “Would that strife might perish from among gods and men!” said Homer, which Heraclitus saw as a denial of things that are just as necessary for existence as their opposites. War, betrayal, wrath… are these simply evils that should not exist? Or are they essential opposites to peace, honesty, and calm, whose tension makes existence itself possible?

Here’s why conflict seems essential to existence. Strife is how change occurs, and change is what existence is. Without it, nothing could come into being or persist. How could there be life without death, peace without conflict, joy without sorrow, fullness without hunger? How could rivers, mountains, and oceans arise without friction, destruction, and transformation elsewhere?

What still troubles me, though, is the role of fire in all this. These ongoing changes Heraclitus writes about… I see them everywhere. I see the weather shifting. I see people entering and leaving the café where I’m writing this. From our imagined ship near the Ephesian shore, we watch the sea endlessly changing its shape, ships coming and going from the harbour, birds darting from place to place.

But where is the fire in all this? I don’t see anything burning when people enter or leave a building, or when clouds pass overhead. So what does Heraclitus mean by fire? Perhaps it has a broader sense: not literal flames, but heat, tension, energy, the conditions that make movement and friction possible. Or perhaps ‘fire’ is more like a metaphor for the process through which things come to be and pass away.

Heraclitean ethics

Heraclitus, despite his misanthropic tendencies, had some wise words about how to live in this ever-changing world full of tension and strife. Unlike his Milesian predecessors, whose philosophies focused almost exclusively on natural phenomena, Heraclitus also treaded the field of ethics.

To live a good life, the most important thing is to understand the Logos. The main goal is wisdom, not fake wisdom only to impress others, but true wisdom, which leads one to see reality for what it is. “The supreme excellence is right thinking and wisdom, which consists in knowing ‘how all things are steered through all things,’” which I quoted from the book Philosophy Before Socrates by Richard McKirahan.

The good life isn’t about understanding alone, McKirahan makes clear. We should actively examine the world and ourselves, “speak the truth and act in accordance with nature”. What that exactly means in practical terms, we can only guess. Oh, and we shouldn’t be drunk, which only makes us stumble and ignorant, so it seems that we won’t get closer to the truth while intoxicated, according to Heraclitus, but only with a clear mind.

Here’s where I want to conclude our trip to Ephesus. I hope you’ve enjoyed the journey so far. Things have been going a bit slowly for this podcast, as I’m focusing on my YouTube channel at the moment. But in the future, I might shift more attention to this project. So, I hope you’ll be willing to wait for other episodes. In the next one, we’ll be sailing the Tyrrhenian Sea toward the city of Elea, where we’ll find a philosopher whose ideas are diametrically opposed to those of Heraclitus.

I hope to see you then,

Thank you for listening.

Sources

Alle woorden (Ben Schomakers)

The Fragments of Heraclitus (Translated by G. T. W. Patrick, Ph.D.)

Early Greek Philosophy (John Burnet)

Philosophy Before Socrates: An Introduction with Texts and Commentary (Richard D. McKirahan)

Presocratic Philosophy: A Very Short Introduction (Catherine Osborne)

A Presocratics Reader: Selected Fragments and Testimonia (Patricia Curd, Richard D. McKirahan)

The First Philosophers (Robin Waterfield)

Online sources

Lives of the Eminent Philosophers (Diogenes Laertius) https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Diogenes_Laertius/Lives_of_the_Eminent_Philosophers/9/Heraclitus*.html

Heraclitus (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy) https://iep.utm.edu/heraclit/

Heraclitus (Standford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/heraclitus/

Heraclitus (Britannica) https://www.britannica.com/biography/Heraclitus

Heraclitus (Wikiquote) https://nl.wikiquote.org/wiki/Heraclitus

Heraclitus: Pre-Socratic Philosophy (Professor Angie Hobbs) (Philosophy Overdose, YouTube)

Introduction to Heraclitus (Academy of Ideas, YouTube)